Since my last blog I’ve been completely absorbed by the Sorgente project. This involved organising 30 hours of performative practice, rostering four facilitators and two research assistants; liaising with two community partners; finding the locations; meeting twenty-five students; collecting observations, think-aloud protocols, audio recordings, photos, sketches, focus groups; a visit to an exhibition on displacement and, on top of it all, dealing with the media who was documenting some of the work. All of this in a post-lockdown climate, where nothing was certain from one day to the next. It was not always fun and games, but it was great to be back in action. The most exciting part was, by far, researching the legend of the Simurgh to prepare for a process drama.

While chasing the Simurgh, I found myself on an epic quest that started with browsing through a collection of postcards over and over; reading a 12th Century poem; comparing the various interpretations of the myth online; getting on Instagram to contact the artist; watching a Turkish TV series; running 7 hours of drama and, ultimately, looking for hidden symbols in the Book of Kells museum. After all that, I feel I know 1% of the Simurgh legend, but I’m more drawn to it than ever. This whole experience was a reminder of how to find my spark (if you watched Soul by Pixar you’ll know what I mean).

But let’s start from the beginning. According to an ancient Persian legend, the Simurgh bird is a timeless flying creature that represents wisdom. It nests in the tree of knowledge, on mount Qaf. It has huge wings and is so old that it has seen the destruction of the world three times. In some representations it features the body of a peacock, claws of a lion and head of a human. In others, it features the scales of a fish and paws of a dog.

It first appeared in writing in The Conference of Birds, a 12th Century Sufi poem written by Farid ud-Din Attar. In the poem, birds from all over the world reunite to elect a leader but, unable to choose, decide to find the Simurgh to ask who should rule the world. The birds embark in an epic journey to find the legendary volatile. Each bird has specific traits, symbolising a human weakness, and they go through a number of valleys representing struggles in life. Along their trajectory, some lose heart and give up. What once was a large flock of birds becomes a smaller flock, with only a few birds making it to mount Qaf. Once there, they cannot find the Simurgh anywhere. They come across a lake and, as they stare at their own reflection, they suddenly realise that the word Simurgh means ‘thirty birds’ and there’s thirty of them left. THEY are the Simurgh.

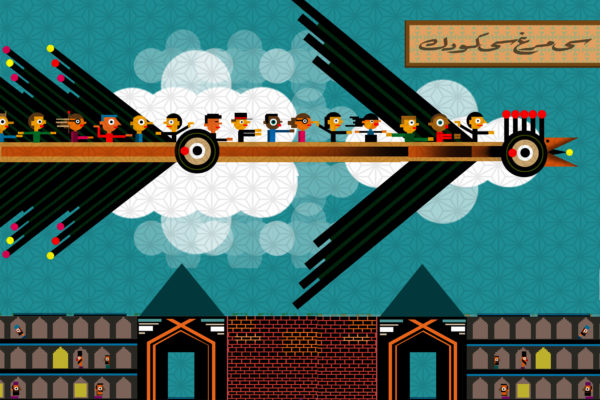

Perhaps it was my affinity with lakes, my love of birds, passion for epic literature, or simply digging a good story, or all of the above, but this legend called me. It is a popular myth in Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. It has been psychoanalysed, studied, televised, fictionalised, turned into songs. I first heard about it from my good friend and colleague Elif Kir. Like everyone in the Sorgente team, I invited Elif to choose one image from Migrations: Open Heart, Open Borders a collection of bird postcards related to an art and migration project. Elif pointed me to the image on page 101, titled ‘Simurgh & 30 Kids’, by Iranian painter Amir Shabanipour (reproduced below with permission from the author). This picture, with its reference to the legend, instantly created a narrative thread to bind all the other bird images in the book.

Only thing was, while in the traditional folklore the Simurgh is shown carrying birds, whales, or elephants, in Amir’s version the bird carries children. I was intrigued by this interpretation and eager to find a frame for the process drama, so I reached out to him on Instagram and asked him to explain his vision. Amir spoke of the Simurgh as a symbol of collective wisdom and self-faith. In his artwork, he depicted migrant children from different cultures of the world riding on the Simurgh, as he believes this is key to build an ideal society, working together while preserving their differences. All very good but I was still stuck to get an entry point to kick off the process drama.

My adventure in chasing the Simurgh legend took me to a Turkish TV series on the story of the Simurgh, again recommended by Elif. Even if I don’t speak Turkish, she said, I would understand. I decided to give it a go (with little hope of success, I confess). The opening sequence is stunning, and you don’t need any Turkish to follow it. In the next scenes, I loved the disorientation of not being able to grasp the narrator as I had to make sense of the visuals to get the gist of the story. A step closer to our participants, some of whom speak very little English.

It was now time to launch the pre-text with the process drama participants, a group of eight young people enrolled in the Access Programme at Yes for Refugees and Migrants. I had my copy of Open Heart, Open Borders; a print out of Amir’s drawing of the Simurgh; cut outs of the birds from the collection; a roll of fabric; and faith that they would engage in the process. However, on the day we were meant to start the 7-hour drama, only two of them turned up. Some had appointments with their case workers; others had to self-isolate due to COVID-19. For reasons of force majeure, we had to cut the 20-hour fieldwork down to 15 hours. No Simurgh in sight.

Youthreach was our second case study, with twelve migrants and their teacher. We scheduled the 15-hour fieldwork differently, this time we made sure that there was enough time for the Simurgh process drama. The group was a bit older, had considerable experience in drama and improvisation. After the workshops on voice, embodied grammar, music, we were ready for the process drama. As a few students were from Afghanistan, I was expecting them to be familiar with the legend of the Simurgh.

My plan was to get them to share their own version of the myth, and to build from what they would bring, finding an angle from their own versions. Great idea but, alas, nobody seemed to be familiar with the story. We started with a movement warm up, then each participant chose an image of a bird from the Open Heart Open Borders collection, and described it in terms of colours, shape, composition, emotion and symbol. I then shared Amir’s imagery of the Simurgh and narrated the legend using simple language. We were interrupted a number of times by latecomers; every time it was an excuse to re-tell the story, and build more details. I asked them to research the legend for homework.

The next day we explored roles, based on the Open Heart Open Borders collection, and we recreated the birds’ trajectory – through a visual map first, then embodying their own question to the Simurgh, and a choreographed piece with music (Garret Scally’s brilliant flocking exercise, which we did in our teacher’s workshop in Feb 2020). The students were divided in two groups, some in charge of the sound effects to recreate a storm, the others in role as the flock of birds. As the storm hit, they used a piece of cloth as a shield and engaged with a frightened bird (Teacher in Role) who had ‘lost her face’. They persuaded her to join them, welcoming her to the flock as one of the family. Once on the mountain, they tried in vain to look for the Simurgh, each with a question to pose.

I’m not ready to share the complete drama structure in this blog. The work is too long and complex to be given justice here. The workshop was audio recorded, pictures taken, and a professional crew came to record the final part of it (but that’s another story). Miriam, in role as research assistant, took meticulous notes of each segment, while the classroom teacher wrote his own commentary of it and another research assistant, as participant observer, described his experience in an interview. Some of the students were also interviewed, and Aisling drew live sketches of the work, which we used as prompts for the final group discussion. It all culminated in a focus group, during which Luca created an impromptu piano composition titled ‘Thirty Notes’. Now we need another six months to analyse the data, before trying to make any sense of it all!

But where does the Book of Kells fit in this story? It was an Irish friend of mine, Pádraig, who noted that the Simurgh pictorial representations reminded him of the Celtic symbology he had carved on his dinner table in Waterford, in the Arklow pottery Tree of Life tradition. That took us to a new twist to explore Celtic folklore, culminating in a guided visit to the famous museum at Trinity where, with some of the Youthreach students, we looked for (and found!) potential versions of the Simurgh in the old manuscript. Good fun, that’s for sure, but the quest isn’t over yet.

As for now, I’m left with a craving to run the workshop again, as I feel it has something to offer – a potential for aesthetic engagement. You know you’ve moved something when the mask covering your face stops bothering you; when you lock eyes with another participant and you feel a shared sense of belonging; when your colleague, normally impeccable at note-taking, tells you she stopped typing because she had tears in her eyes. And you know it, because you also felt tears coming. It is a privilege to witness those rare moments in drama when the fictional frame intersects the real frame on a metaphorical level; when age, culture, and other gaps temporarily disappear. When time stops. In those moments we’re shaken out of routine into existence. That’s when we remember, ever so briefly, what our spark is.

Amir Shabanipour, The Simurgh & 30 Kids. From Migration: Open Heart, Open Borders.

1 Comment. Leave new

Thanks for sharing this beautiful experience here. It will be helpful to lots of practitioners in drama and inspire them I believe. I have felt that I took the same journey with you while I was reading. Big congratulations to you as a facilitator. Hopefully, you will continue workshops based on the legend. It would be food for thought to see different variations of it with different groups.