Last week, I mentioned using zines as as a research tool. Today, I pause to reflect on my three experiences with zines so far: 1) as a zine-maker during a training session; 2) as a zine-facilitator with a group of students; 3) as a zine-trainer in a one-on-one session.

Before I start, you may wonder what a zine actually is. A zine is a hand-made (yes, hand-made) DYI booklet that can contain lists, text, poetry, sketches, comics or collage – often a combination of them all. Its purpose may be spreading political ideas, inciting action, triggering self-expression or, in my case, eliciting self-reflection. Zines come in various sizes; the most popular one is the pocket zine, a 7×10 cm cutie that fits into your pocket.

Zine-making has been around since the 18th century. Short for fanzine, or magazine, zine-making is a grassroots, informal activity that can be traced back to pamphlets in 1770s; the Harlem movement in 1920s; science fiction in 1930s; beat poetry 1940s; anti-war and feminist manifestos 1950-60s; the punk scene in 1970-80s; riot grrrl bands in 90s. Today, zines communities exist online (search for #zines on Instagram, you’ll see).

Zine-making can work well with second language learners, as re-purposing through collage can help bypass the language barrier to create identity texts (see Cummins & Early). It can be a helpful reflective tool after a drama workshop to elicit reflection on a given topic. It can also be used before a workshop, to draw out expectations. It’s low-cost, quirky, doesn’t require a fast wifi connection and, most importantly, it’s fun.

I was introduced to zine-making in November 2020, in a very formal setting: I was on the PhD confirmation panel for Autumn Brown, an American researcher who is using zines as a methodological tool in an art-science study, as part of SySTEM 2020 project. It was a poignant, honest discussion panel which, I’m sure, neither Autumn nor I will forget any time soon.

Autumn’s first PhD case study, Zine, focuses on prototyping zines as a reflective evaluation research tool, drawing on Ryan and Ryan’s 4Rs reflective framework. She worked in informal learning contexts from across Austria, Slovenia, Greece and Ireland, engaging different age groups and community cohorts, including families in Direct Provision, in a series of practice-based workshops.

I was intrigued by Zines as an embodied research tool. After the academic formalities were over, I invited Autumn to lead a zine-making training session with the Sorgente team. She kindly agreed and instructed us to get a A4 piece of paper, colours, an old magazine, scissors a glue stick. Assembling this stuff was a joyous endevour, I even got to use the watercolour set from my two-year old’s arts and craft box!

Autumn took us thorugh a step-by-step zine-making training process. My most vivid memory is the folding ritual. The skilful way she handled the A4 sheet of paper was theatrical. That piece of paper ceased to be an object; it became a prop. There was a ritualised, performative element in each step of the folding process, at its highest as she covered her face with the paper and peeked at us through the fold’s cut.

After the folding ritual, she gave us one prompt at the time, with 10 minutes in-between to address them through text and image – chill out music in the background. The four prompts were:

- What do you wish people knew about learning another language?

- What aspects of Sorgente are you most excited about?

- What do you imagine will be the biggest impacts of Sorgente?

- What is your favourite part about teaching or learning a new language?

We took an hour in total to work our way through these prompts, one per page or spread, using text, poetry, collage, sketches. After we finished, we all shared our zines. It was an incredibly useful exercise to do, just before kicking off the Sorgente data collection, as it gave us the opportunity to share each other’s values – a crucial team-building exercise as we were about to co-facilitate 10 workshops.

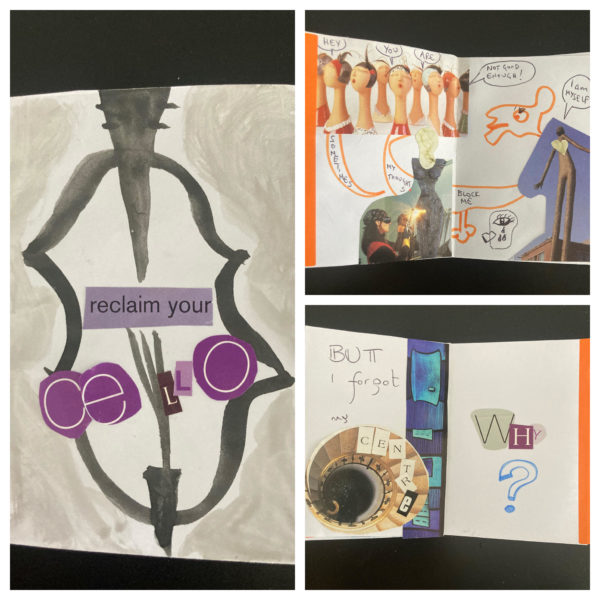

But it wasn’t just gold for team building; it was also priceless to reflect on my own expectations, hopes, fears as the project lead. It was a tool for self-reflection, generating an identity text. The 10 minutes from one reflective prompt to the next literally flew. I was totally absorbed, in a flow state. By the end of it, I was greeted by this cute little artefact, furnished with shapes and blotches of my values on its folded paper.

According to my zine, what I love about teaching is seeing a person grow; what I love about learning a new language is opening a window into a new way of living, without losing my own feet. The aspect of Sorgente I was most excited about was savouring the physical and performative group presence (understandably, after 15 months of Digital Displacement).

According to my zine, what I wish others knew about language learning is that I can have more than one identity as an L2 learner, but I can still be my SELF. Trying different personae is not shameful – even when the role I’m playing in society is the one who does not know how to pronounce x; or the meaning of y. These insights, and others, emerged spontaneously during the zine-making creative process.

My second experience was totally different. It was in class, with our research participants, eight young students enrolled in the YES for refugees and migrants Access program, Sorgente’s community partner. Miriam and I brought in a range of material from stickers, ribbons, magazines and art work from the Migration: Open Heart Open Borders Project. The three reflective prompts (which Autumn help me to articulate) were:

- What do you wish people knew about learning English?

- What surprised you about last week’s activity (language body map)?

- What do you think learning English through the arts will be like?

I wrote them on signs, in big characters. I also got them translated into French, Arabic, Somali and Pashto. The students were a bit overwhealmed at first (meta-reflection? No right or wrong? Just tell me what to write) but once they clicked, they wouldn’t stop. Some had creative anxiety (teacher, I can’t draw!); others totally deviated from the prompts and did their own thing. By the end of the hour, there was a sense of urgency and care.

My experience of it was stressful: I was scared I would forget some step in the folding ritual (though I didn’t, but I had eight pre-made booklets, as back ups). Here, my anxious teacher self was trying to contain, or control, what is meant to be a joyful but messy activity (the fold). Luckily I practiced folding in advance, so it all worked out. During the process, instead of sitting back and enjoying the OKA music, I was running around like a madwoman. It felt like like Master Chef: 5 minutes remaining! 3 minutes remaining!

Later, I spent hours documenting the 64 images (8 images x 8 zines) as JPEGs and PDFs. Downloading, cropping, combining, scanning, analysing. I was zined-out! It’s too early now to get a sense of the data. What I can get a sense of, however, is that I need to relax into it and try to get into the flow of zine-facilitating just as I got into the flow of zine-making. I need to commit to the ritualised, performative element of it.

My third experience was more intimate. It was just me and Luca, the music education man of Sorgente, friend, colleague and partner-in-crime. Luca couldn’t make it for Autumn’s training, but may use zines to reflect on his music sessions next week, so I gave him a sample training (train-the-trainer kind of thing). Again, OKA music in the background and colours, pens, magazines, scissors. The reflective prompts for Luca’s session were:

- What do you wish people knew about music education?

- Does this relate to anything you have learnt during your PhD?

- How does your music practice impact society?

Autumn suggested always making your own zine, even when facilitating. I couldn’t do that in class, so I tried during Luca’s session. While he pondered on music education, I examined my own relationship with music as a student. I’ve studied the cello for 15 years now. It was a reality-check for me, an emotional acknowledgement of the demons in my head. Zine-making helped me to pin down a performance anxiety that has crippled me for years. As we shared our work, seeing my voice impressed on paper was powerful.

Too powerful. So powerful, in fact, that I didn’t really listen to him (if you’re reading this, sorry Luca). I was nodding, but I was still processing my own reflection. I was too absorbed by the reverberation of my own zine-making. In that respect, I failed him as a zine-facilitator. I was OK as a trainer, I guess, as I demonstrated what needs to be done (I nailed the theatricality of fold). But as I didn’t listen to his presentation, I didn’t fully commit.

Next step is to work again with the eight young people, getting them to generate zines as identity texts to reflect on music composition as a tool for language learning. Zine-making is simple, but not easy: it requires a level of abstraction, an ability to meta-reflect, to break down complex ideas and express them through visuals. Most importantly, it requires committment. Not only as a zine-maker, but also as a zine-facilitator.